Low back pain, leading cause of disability, must be addressed

By Evangeline T. Capuno

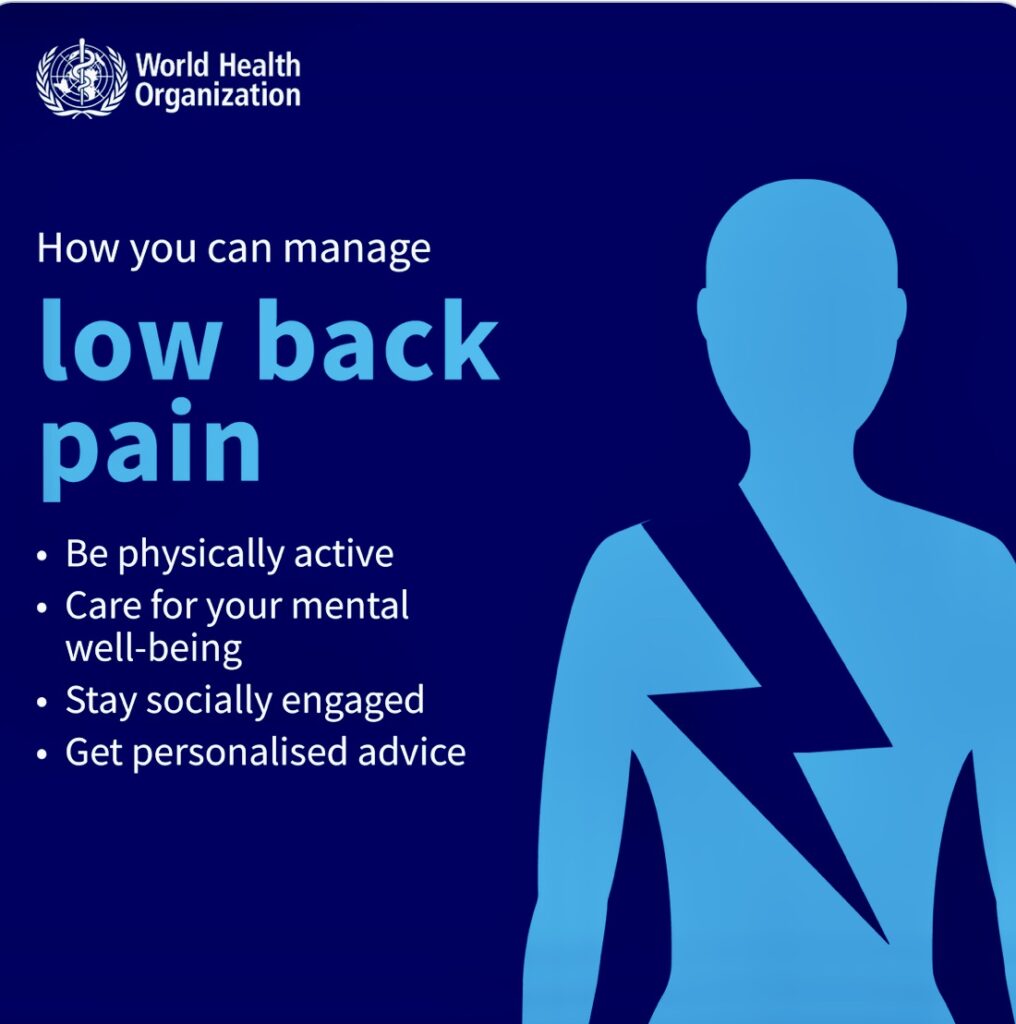

Low back pain (LBP) – described as the pain between the lower edge of the ribs and the buttock – is the leading cause of disability globally, according to the Geneva-based World Health Organization (WHO).

In 2020, approximately one in 13 people, equating to 619 million people, experienced LBP, a 60% increase from 1990.

“Cases of LBP are expected to rise to an estimated 843 million by 2050, with the greatest growth anticipated in Africa and Asia, where populations are getting larger, and people are living longer,” the WHO said in a new report.

“To achieve universal health coverage, the issue of low back pain cannot be ignored, as it is the leading cause of disability globally,” said Dr Bruce Aylward, WHO Assistant Director-General, Universal Health Coverage, Life Course. “Countries can address this ubiquitous but often-overlooked challenge by incorporating key, achievable interventions, as they strengthen their approaches to primary health care.” So much so that the WHO released its first-ever guidelines on managing chronic low back pain (LBP) in primary and community care settings.

Interventions

With the guidelines, WHO recommends non-surgical interventions to help people experiencing chronic primary LBP. These interventions include: education programs that support knowledge and self-care strategies; exercise programs; some physical therapies, such as spinal manipulative therapy and massage; psychological therapies, such as cognitive behavioral therapy; and medicines, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medicines.

The guidelines outline key principles of care for adults with chronic primary LBP, recommending that it should be holistic, person-centered, equitable, non-stigmatizing, non-discriminatory, integrated and coordinated.

The WHO said care should be tailored to address the mix of factors (physical, psychological, and social) that may influence their chronic primary LBP experience. A suite of interventions may be needed to holistically address a person’s chronic primary LBP, instead of single interventions used in isolation.

WHO advises against interventions such as: lumbar braces, belts and/or supports; some physical therapies, such as traction (i.e. pulling on part of the body); and some medicines, such as opioid pain killers, which can be associated with overdose and dependence.

Chronic disease common among adults

LBP is a common condition experienced by most people at some point in their life. “People at any age can experience LBP, including children and adolescents,” the WHO said. “The peak in the number of cases occurs at 50–55 years, and women experience LBP more frequently than men.”

The prevalence and disability impact of LBP are greatest among older people aged 80–85 years. Recurrent LBP episodes are more common with ageing.

LBP can be specific or non-specific. Specific LBP is pain that is caused by a certain disease or structural problem in the spine, or when the pain radiates from another part of the body. Non-specific LBP is when it isn’t possible to identify a specific disease or structural reason to explain the pain.

“LBP is non-specific in about 90% of cases,” the United Nations health agency said.

According to the WHO, the personal and community impacts and costs associated with LBP are particularly high for people who experience persisting symptoms. Chronic primary LBP referring to pain that lasts for more than 3 months, that is not due to an underlying disease or other condition – accounts for the vast majority of chronic LBP presentation in primary care, commonly estimated to represent at least 90% of cases.

Chronic LBP is a major cause of work loss and participation restriction, and reduced quality of life around the world. Considering the high prevalence, LBP contributes to a huge economic burden on societies. It should be considered a global public health problem that requires an appropriate response.

Signs and symptoms

Low back pain can be a dull ache or sharp pain. It can also cause pain to radiate into other areas of the body, especially the legs.

“LBP can restrict a person’s movement, which can affect their work, school, and community engagement. It can also cause problems with sleep, low mood, and distress,” the WHO stated, adding that LBP can be acute (lasting under 6 weeks), sub-acute (6–12 weeks) or chronic (over 12 weeks).

In most cases of acute LBP, symptoms go away on their own and most people will recover well. However, for some people the symptoms will continue and turn into chronic pain.

People with LBP may also experience spine-related leg pain (sometimes called sciatica or radicular pain). This is often described as a dull sensation or a sharp, electric shock feeling. Numbness or tingling and weakness in some muscles may be experienced with the leg pain.

When associated with LBP, radicular signs and symptoms are often due to involvement of a spinal nerve root. Some people may experience radicular symptoms without LBP, when a nerve is compressed or injured distal to the spinal column.

All these experiences affect well-being and quality of life and often lead to loss of work and retirement wealth, particularly in those who experience chronic symptoms.

Life quality

The WHO noted that LBP affects life quality. More often than not, LBP is associated with comorbidities and higher mortality risks. “Individuals experiencing chronic LBP, especially older persons, are more likely to experience poverty, prematurely exit the workforce, and accumulate less wealth for retirement,” the UN health agency said.

In addition, older people are more likely to experience adverse events from interventions, reinforcing the importance of tailoring care to the needs of each person. “Addressing chronic LBP among older populations can facilitate healthy ageing, so older persons have the functional ability to maintain their own well-being,” the WHO said.

In 2020, LBP accounted for 8.1% of all-cause years lived with disability globally. Yet clinical management guidelines have been developed predominately in high-income countries.

“Addressing chronic low back pain requires an integrated, person-centered approach. This means considering each person’s unique situation and the factors that might influence their pain experience,” said Dr Anshu Banerjee, WHO Director for Maternal, Newborn, Child, Adolescent Health, and Ageing. “We are using this guideline as a tool to support a holistic approach to chronic low back pain care and to improve the quality, safety and availability of care.” – ###