Mobile phones have revolutionized modern healthcare. Doctors use them for rapid access to clinical guidelines, medication references, teleconsults, patient coordination, and emergency communication. Nurses rely on them for shift updates, medication reminders, and alerts. But an increasing body of evidence warns that these indispensable tools may also be serving as silent vectors of infection inside hospitals.

By Rebecca L. Castillo, MD

A Potential Vector in the Clinical Environment

The typical healthcare worker touches their phone dozens—sometimes hundreds—of times per shift. From the nurses’ station to the bedside, from the hallway to emergency calls, the mobile phone is always within reach.

Yet, unlike stethoscopes, medical equipment, or even hands—each reinforced by well-established cleaning protocols—phones remain largely unregulated, inconsistently cleaned, and frequently exposed to contaminated environments.

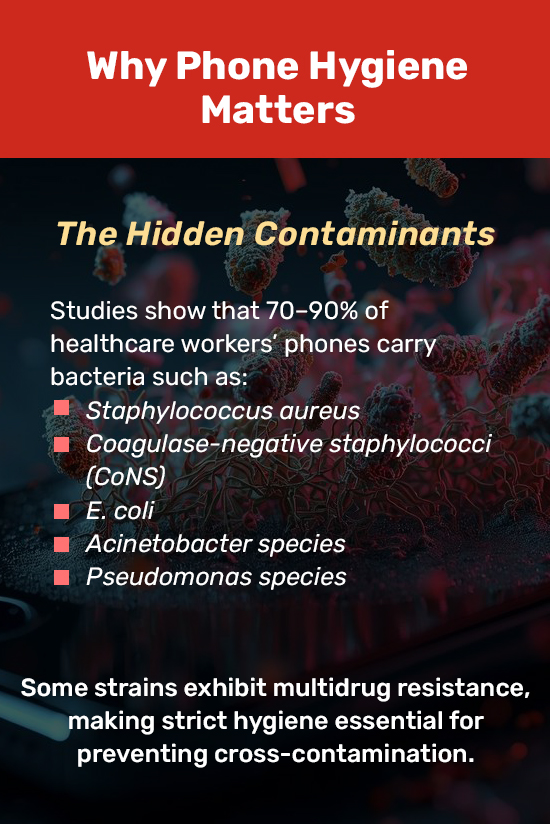

Multiple studies have documented that healthcare workers’ phones harbor a wide range of pathogens, including:

- Staphylococcus aureus

- Coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS)

- Escherichia coli (E. coli)

- Acinetobacter species

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa

These bacteria are not benign. Many of them have been implicated in healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) such as bloodstream infections, ventilator-associated pneumonia, wound infections, and sepsis. Even more concerning, some isolates demonstrate multidrug resistance, making potential infections more difficult to treat.

The University of the Philippines-Philippine General Hospital Infection Control Unit’s (HICU’s) internal review mirrors global findings. “Phones go everywhere with us,” the advisory notes. “They are touched, placed, and handled repeatedly throughout a shift. Without strict hygiene, they can become reservoirs of infection.”

Why Phones Are So Dangerous in a Hospital Setting

Several factors contribute to the high contamination potential of phones:

1. Constant Handling

Phones are touched with ungloved hands, gloved hands, hurried hands. They are checked between tasks, during transitions, or during breaks—often without immediate handwashing afterward.

2. Warmth and Surface Texture

The temperature generated by mobile devices creates a conducive environment for bacterial survival and growth.

3. Use in High-Risk Areas

Phones are frequently used near:

- Bedside monitors

- Invasive lines

- Patient beds

- Isolation rooms

- Procedure tables

In such settings, even fleeting contamination can be clinically significant.

4. Rare Disinfection

Most phones are not cleaned regularly or appropriately. Alcohol wipes may be available, but few staff have protocols reminding them to disinfect after every shift or after entering patient areas.

5. Shared Devices

Passing a mobile device from one staff member to another—during code blue situations, endorsements, or checking labs—amplifies the risk of cross-contamination.

As one infection control nurse described: “The phone is the one item everyone touches but no one disinfects.”

When the Risk Becomes Reality

Although many mobile-phone–related contamination events remain unreported, HAIs have long been linked to lapses in environmental and hand hygiene. Pathogens transferred from phones to hands can be passed to patients through:

- Palpation

- Adjusting oxygen masks

- Touching IV lines

- Administering medications

- Handling wounds

- Placing catheters

For critically ill patients—especially those in the ICU—such microbial exposures can trigger infections that prolong hospital stay, compromise recovery, or lead to severe complications.

The HICU emphasizes that this is not theoretical. Contaminated devices have been implicated in outbreaks involving MRSA, Acinetobacter, and Pseudomonas, particularly in high-acuity units.

The HICU’s Recommended DOs and DON’Ts

To protect both patients and healthcare workers, the HICU has issued a clear, practical set of guidelines. These should ideally be integrated into every hospital’s infection control protocols.

DOs

- Disinfect your phone at least once per shift or after use in clinical areas.

Regular disinfection reduces the bacterial load by up to 95% in some studies.

- Use 70% isopropyl alcohol wipes or approved disinfectants for phones.

These agents kill a broad spectrum of pathogens without damaging modern device screens.

- Wash or sanitize your hands after using your phone—especially before touching patients or clinical equipment.

Hand hygiene remains the single most effective measure to prevent HAIs.

- Limit phone use to designated areas such as staff lounges and call rooms.

Keeping devices away from bedside and procedure areas dramatically reduces contamination risk.

DON’Ts

- Do not use your phone at the bedside or inside isolation rooms.

This significantly increases the chance of transmitting pathogens between patients.

- Avoid placing your phone on patient beds, chairs, or procedure tables.

These surfaces often harbor microbes invisible to the eye.

- Do not answer your phone while wearing gloves.

This contaminates both the gloves and the device, undermining sterile technique.

- Do not share your phone during procedures or patient rounds.

A shared device is a shared vector. Avoid unnecessary passing of phones between staff.

A Culture of Safety: The Ultimate Goal

Infection control is not just a set of rules—it is a culture. The HICU stresses that adherence to mobile phone hygiene is not about administrative compliance; it is about protecting lives.

In the ICU, every second is critical, and every contact matters. An overlooked phone can carry enough microbial load to initiate an infection in a high-risk patient.

“The small habit of disinfecting your phone,” the advisory states, “can have a life-saving impact.”

But real change requires consistency. Just as handwashing and PPE use became ingrained through hospital-wide education, visual reminders, and leadership modeling, mobile phone hygiene must now be treated with the same level of priority.

Toward Stronger Infection Prevention in the Philippines

As Philippine hospitals continue to modernize and become increasingly dependent on digital communication, mobile phones will remain an unavoidable part of clinical workflows. Therefore, infection prevention strategies must evolve accordingly.

Healthcare workers can take simple, immediate steps:

- Carry alcohol wipes or keep them accessible at stations.

- Set reminders to disinfect phones at the start and end of shifts.

- Advocate for unit-wide policies on device use.

- Model proper behavior during rounds.

Hospital administrators can also support change by:

- Providing disinfectant-compatible wipes in all units

- Installing posters on phone hygiene in key areas

- Including device hygiene in orientation and reorientation programs

- Encouraging regular audits of compliance

Taken together, these measures reinforce a culture of accountability and vigilance—values central to patient safety.

Conclusion: Clean Hands, Clean Devices, Safer Patients

Mobile phones are not going away. They are essential tools in modern healthcare—tools that save time, streamline communication, and support patient care. But without proper hygiene, they can also become dangerous vectors in clinical environments.

Hospitals must treat phone disinfection as a fundamental element of infection prevention and control. For healthcare workers, the practice is simple, quick, and highly impactful.

In critical care settings, where the most vulnerable patients reside, something as small as a clean phone may truly make the difference between harm and healing.

References

- Zenbaba D, et al. Mobile phone contamination and its significance in healthcare settings: A systematic review. Journal of Infection Prevention. 2023.

- Mushabati T, et al. Bacterial contamination of mobile phones among healthcare workers: Prevalence and infection control implications. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021.

- Munoz-Price LS, et al. Mobile devices in healthcare settings: Infection risks and recommendations. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology. 2017.

- Brady RR, et al. Review of mobile communication devices and their potential role in transmission of nosocomial pathogens. Journal of Hospital Infection.

- World Health Organization. Health-care associated infections: Fact sheet. WHO.

- CDC. Infection control guidelines and recommendations for healthcare settings. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- HICU Advisory Memo on Mobile Phone Hygiene (2025).