iabetes has become so common in the Philippines that it is often treated as inevitable—almost a rite of passage of aging. In clinics and hospitals, physicians regularly meet patients whose diabetes is discovered only after complications appear: blurred vision, numb feet, stubborn wounds, kidney failure, or a first heart attack. By then, the question is no longer how to prevent damage, but how much damage can still be controlled.

This is the central failure we must confront: diabetes is not being found early enough.

Type 2 diabetes does not suddenly arrive. It develops quietly over years, beginning with insulin resistance and rising blood sugar levels that often cause no pain, no fever, no alarm. During this silent phase, blood vessels are already being injured, kidneys slowly strained, nerves gradually dulled. By the time symptoms become obvious, the disease is already well-established.

The science, however, is no longer in doubt. Early detection works. Routine screening using fasting blood sugar or HbA1c can identify diabetes and prediabetes long before complications arise. Lifestyle interventions started early can delay or even prevent progression. Appropriate medications, when introduced on time, reduce the risk of heart attack, stroke, kidney failure, blindness, and amputation. Diabetes, when caught early, is one of the most manageable chronic diseases in medicine.

What the Philippines lacks is not knowledge—but systematic action.

Screening remains inconsistent and often symptom-driven. High-risk Filipinos—those with family history, central obesity, hypertension, prior gestational diabetes, or sedentary lifestyles—are not routinely flagged early. Many only encounter testing during hospital admission or pre-employment exams, long after opportunities for prevention have passed.

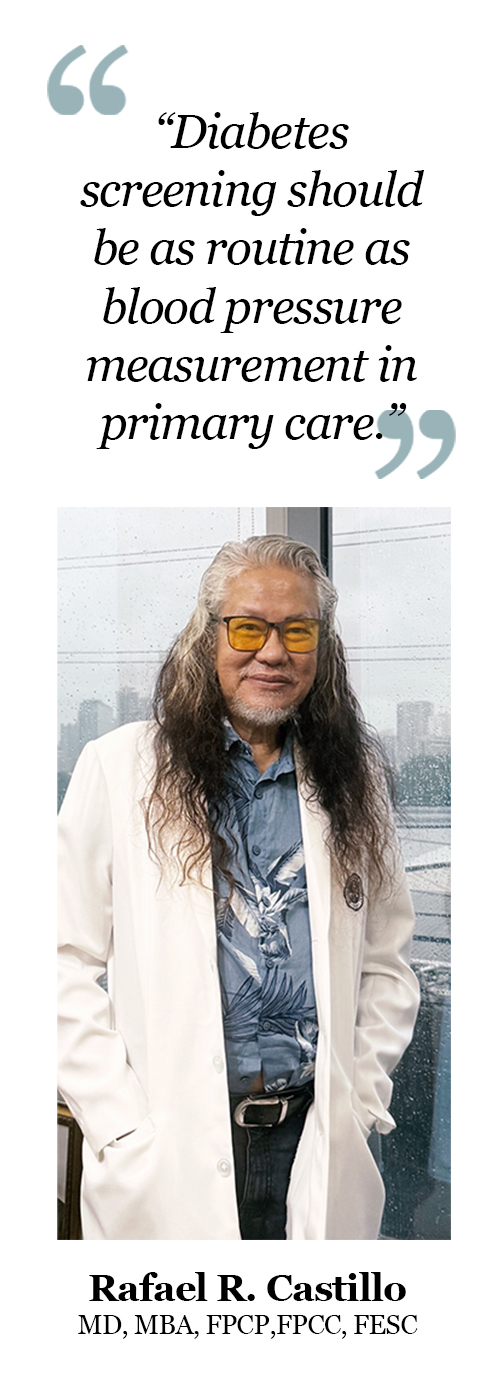

This must change. Diabetes screening should be as routine as blood pressure measurement in primary care. Prediabetes should be treated as a warning signal, not a footnote. The first months after diagnosis should trigger structured follow-up, not delayed return visits. Existing mechanisms—such as PhilHealth’s Konsulta program—must be strengthened and normalized as the front line of detection, not an afterthought.

Diabetes is not just a personal health issue; it is a national systems issue. Every delayed diagnosis increases future healthcare costs, productivity losses, and family hardship. Every early diagnosis is a chance to protect organs, preserve livelihoods, and prevent suffering.

The goal is not perfection. It is earlier action.

Because in diabetes care, the most powerful intervention is often the simplest—and the most overlooked: finding the disease before it finds the patient.