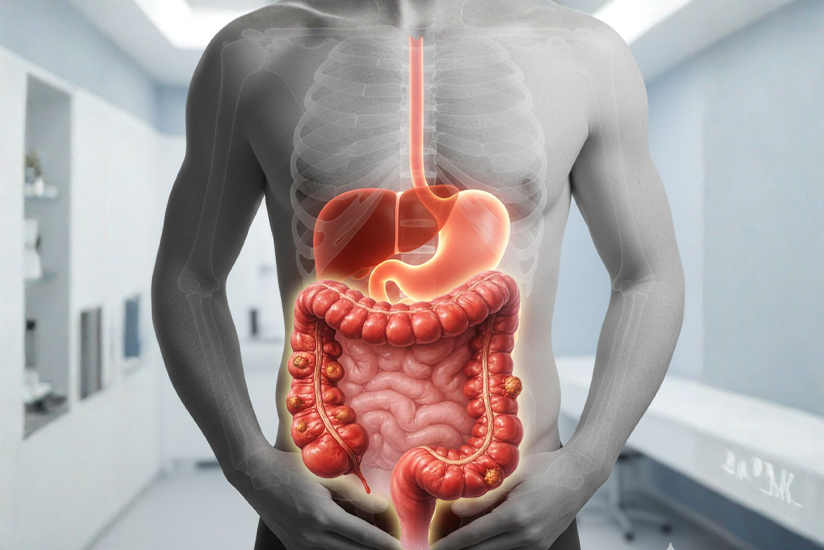

Diverticulosis—small pouch-like bulges in the colon wall—is often discovered by accident during colonoscopy, usually in older adults who felt perfectly fine. Yet these “silent pouches” can become a major source of lower GI bleeding, recurrent abdominal pain, and acute diverticulitis that mimics appendicitis—especially in Asian populations where right-sided disease is common. In the Philippines, local colonoscopy-based studies suggest diverticulosis is far from rare, particularly among seniors, and its burden will likely rise as the population ages and dietary patterns shift. This cover story explains what diverticulosis is, why it forms, who is at risk, and what evidence-based prevention and treatment look like—without myths, panic, or unnecessary restrictions.

By Rafael R. Castillo, MD

The Philippines snapshot: how common is it, really?

Diverticulosis is tricky to measure because most people have no symptoms and will never know they have it unless they undergo colonoscopy or imaging. That means “true community prevalence” is hard to pin down in any country—more so in places where colonoscopy access is uneven.

Still, Philippine hospital-based data offer a useful window:

- In a colonoscopy-based review at Baguio General Hospital (2011–2016), 362 of 2,565 patients had diverticulosis—a prevalence of 14%. The majority were in the 6th to 8th decade of life, and the most common location was the ascending colon (42%), consistent with the Asian pattern.

- An older Cebu hospital profile (radiology/surgery-based) reflects how diverticular disease appears in clinical practice (often later, often symptomatic), but it is not designed to estimate population prevalence.

Bottom line: In Philippine colonoscopy cohorts, diverticulosis can be common—especially in older adults—and may often involve the right colon, aligning with broader Asian observations.

Pathophysiology: why do these pouches form?

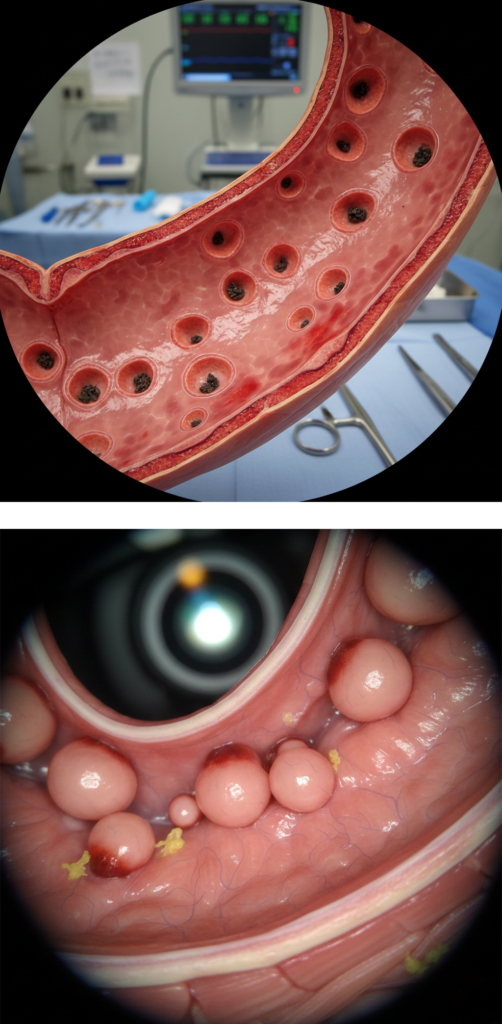

A diverticulum is a sac-like protrusion of the inner lining of the colon through weak points in the muscular wall—often where blood vessels penetrate. Most colonic diverticula are “false” diverticula (mucosa/submucosa herniating outward).

Diverticulosis is thought to arise from a combination of:

- Structural wall changes (connective tissue remodeling and altered collagen patterns) and

- Motility/pressure forces—segments of colon generating higher, uncoordinated pressures over time, contributing to herniation at weak spots.

Why location differs in Asia

In Western countries, diverticulosis is classically left-sided (sigmoid). In many Asian populations, it is more commonly right-sided—and may present at a younger age, suggesting a stronger genetic or anatomic component.

Risk factors: who is more likely to develop diverticulosis and complications?

The strongest consistent risk factor is age—diverticulosis becomes more common as people get older.

Other risk factors linked to diverticular disease and diverticulitis in studies and guidelines include:

- Low fiber dietary patterns (associated with higher risk of symptomatic disease in many studies)

- Overweight/obesity and metabolic risk

- Physical inactivity

- Smoking

- Regular NSAID use (in multiple cohorts, associated with complications)

And in Philippine data, diverticulosis and diverticular bleeding tended to cluster in older adults, with a notable proportion presenting for lower GI bleeding.

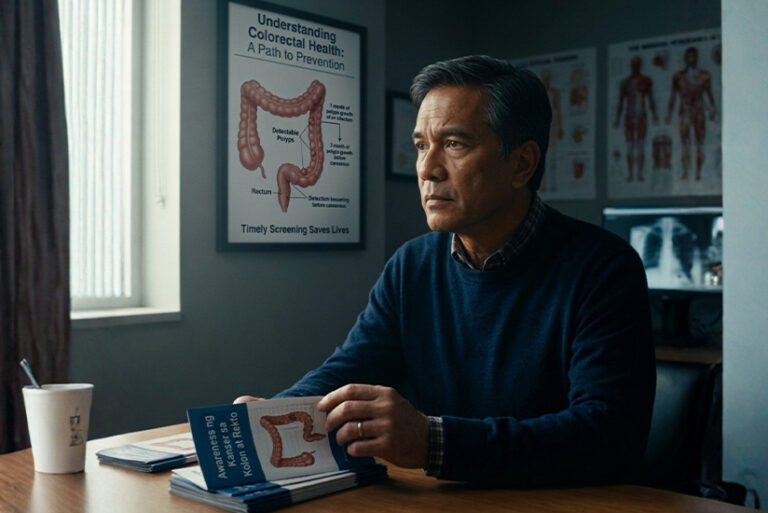

Treatment: what’s evidence-based (and what’s outdated)

1) If you have diverticulosis but no symptoms

Most people need no medication. Focus is on risk reduction:

- Fiber-forward eating pattern, adequate fluids, regular activity

- Avoid tobacco; manage weight and cardiometabolic risk

2) If you have acute diverticulitis (suspected)

Diverticulitis is a medical diagnosis—often confirmed by imaging when needed. Modern guidance has shifted: in mild, uncomplicated diverticulitis among immunocompetent patients, antibiotics may be used selectively rather than routinely, with close follow-up and supportive care.

When antibiotics, hospitalization, or surgery are more likely:

- severe pain, persistent fever, inability to tolerate oral intake

- immunocompromised state

- suspected complications (abscess, perforation, obstruction)

3) If there is diverticular bleeding

Bleeding can be brisk and painless. It may stop spontaneously but can require urgent evaluation, colonoscopy-based management, or hospitalization depending on severity. Philippine data show diverticular bleeding occurring in a subset of diverticulosis patients, more common in older adults. quality and fiber intake.

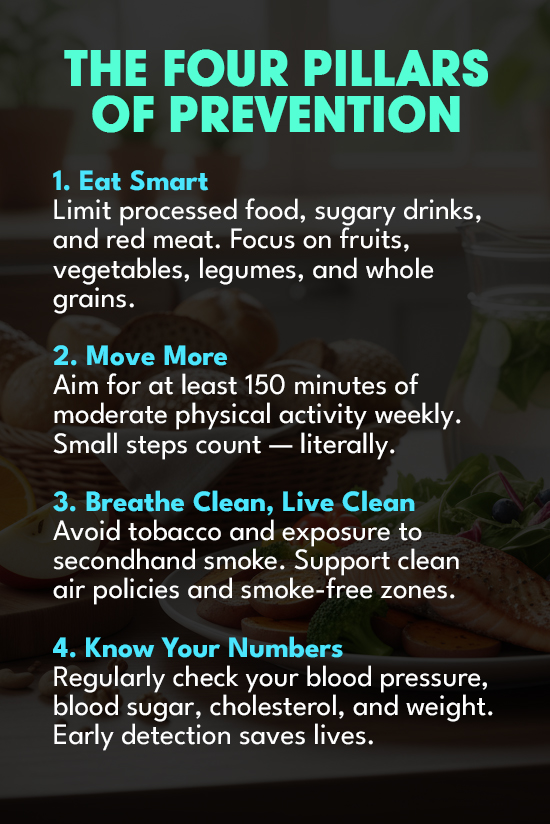

Prevention: the “boring” habits that protect you

No strategy eliminates diverticulosis entirely—age and anatomy matter. But evidence consistently supports lowering the risk of symptomatic disease and diverticulitis through lifestyle:

- Eat more fiber-rich foods (vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains) and consider fiber supplementation if advised

- Move regularly (walking counts; consistency matters)

- Maintain a healthy weight

- Avoid smoking

- Be cautious with frequent NSAID use and discuss safer options with a clinician if needed

The take-home message for Filipino families

Diverticulosis is common enough in Philippine colonoscopy cohorts that it should be treated as a normal aging-associated finding—not a diagnosis to fear. The real win is preventing complications: build a fiber-forward plate, keep the body moving, avoid smoking, manage weight, and treat warning signs early.

And perhaps the most important perspective: diverticulosis is not a life sentence. For many, it is simply a reminder that the colon, like the rest of the body, ages best when it is fed well and used daily.

“Diverticulosis is common, often silent, and usually harmless—until it isn’t. The goal is not fear, but fiber, fitness, and fast action when warning signs appear.”

References

- HERDIN. Prevalence and Clinical Characteristics of Colonic Diverticular Disease at Baguio General Hospital Endoscopy Unit 2011–2016 (COVERT-6).

- World Gastroenterology Organisation (WGO). Global Guideline: Diverticular Disease (English). Definitions; global/Asian distribution; management overview.

- Talutis SD, et al. Pathophysiology and Epidemiology of Diverticular Disease. (Review, PMC).

- American Gastroenterological Association (AGA). Medical management of colonic diverticulitis (Clinical guidance: selective antibiotic use; diet during acute phase).

- American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS). Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Left-Sided Colonic Diverticulitis (2020).

- Bailey J, et al. Diverticular Disease: Rapid Evidence Review. American Family Physician (2022).

- Prasad S, et al. Nuts, corn, and popcorn and the incidence of diverticular disease. (Evidence summary, PMC).

- Mayo Clinic. Diverticulitis diet: Do nuts, seeds, and popcorn trigger an attack? (Patient guidance reflecting evidence).

- Cebu Doctors Hospital profile (HERDIN). A clinical profile of diverticular disease of the colon among Filipinos (1984–1988).

- Turner GA, et al. Epidemiology/Etiology of Right-Sided Colonic Diverticular Disease (Asian distribution context).

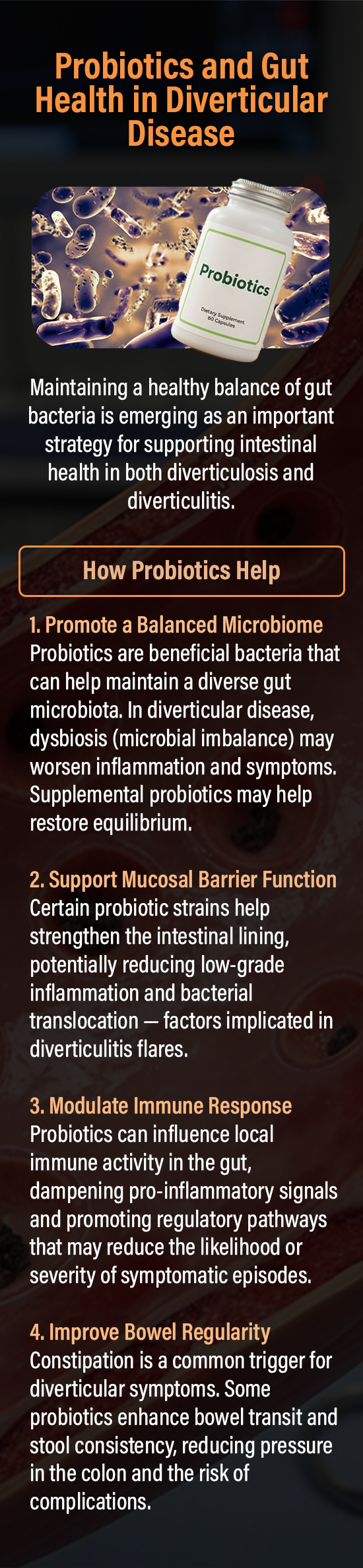

PROBIOTICS IN DIVERTICULAR DISEASE

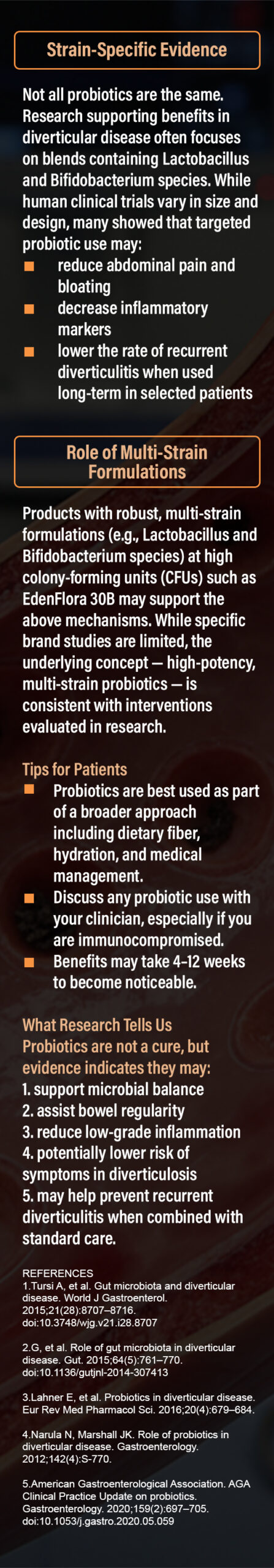

(EVIDENCE TABLE)

| Evidence Area | Key Findings | Source |

| Gut dysbiosis in diverticular disease | Altered microbiome linked to symptoms | Tursi et al., World J Gastroenterol, 2015 |

| Probiotics & symptom relief | Reduced abdominal pain, bloating | Barbara et al., Gut, 2015 |

| Inflammation modulation | Probiotics reduce low-grade mucosal inflammation | Lahner et al., Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci, 2016 |

| Recurrence prevention | Probiotics + standard care ↓ recurrence | Narula & Marshall, Gastroenterology, 2012 |

| Safety | Generally safe in immunocompetent adults | AGA Clinical Practice Update, 2020 |